» It is appropriate to think of law in South East Asia geologically, as a series of layers each of which overlays the previous layers without actually replacing them, so that in places, due to tectonic shifts, the lower layers are still visible, although not perfectly distinguishable from each other. « – Andrew Harding1

What does it mean for a country’s legal system to modernise without colonisation? Applying Professor Harding’s geological analogy, the answer for Siam seems to lie beneath tectonic layers of law, culture, and reform – with the willingness to push forward change being the main tectonic force that caused the shifts.

Siam’s law reform in the 19th and early 20th centuries may be thought of as comprising two main parts: the reform of substantive law and the reform of the judicial system. Focusing on the first, we argue for a more comprehensive understanding of the reform process, to encompass the true complexities involved. Rather than a seamless transition from traditional to modern law, Siam’s legal reform may be thought of as piecemeal and shaped by multiple, overlapping influences. Accordingly, any research into the reform process should accommodate the many spheres of influence, not only from the obvious source that is pressure from colonial powers, but also from the much less discussed latent impetus.

For this blog post, we have chosen two aspects that highlight this complexity: our presupposition of the nature of “traditional law” and the under-acknowledged influence of the people who personified the law reform.

The Elastic Nature of Siam’s Traditional Law

There is no single accepted narrative of Siam’s legal history, and the roles that various factors played in the country’s legal development continue to be debated. However, for the purpose of this blog post, it is useful as a starting point to draw on the work of the late eminent Thai scholar Professor Preedee Kasemsup,2 according to whom Thai legal history may be divided into two broad eras: “pre-modern” or “traditional” law, and “modern” law.3 The former refers to the laws of previously ruling states in the geographical area of today’s Thailand (the Sukhothai, Ayutthaya and early Bangkok periods), while the modern era began with the reform period and continues to present-day Thailand.4

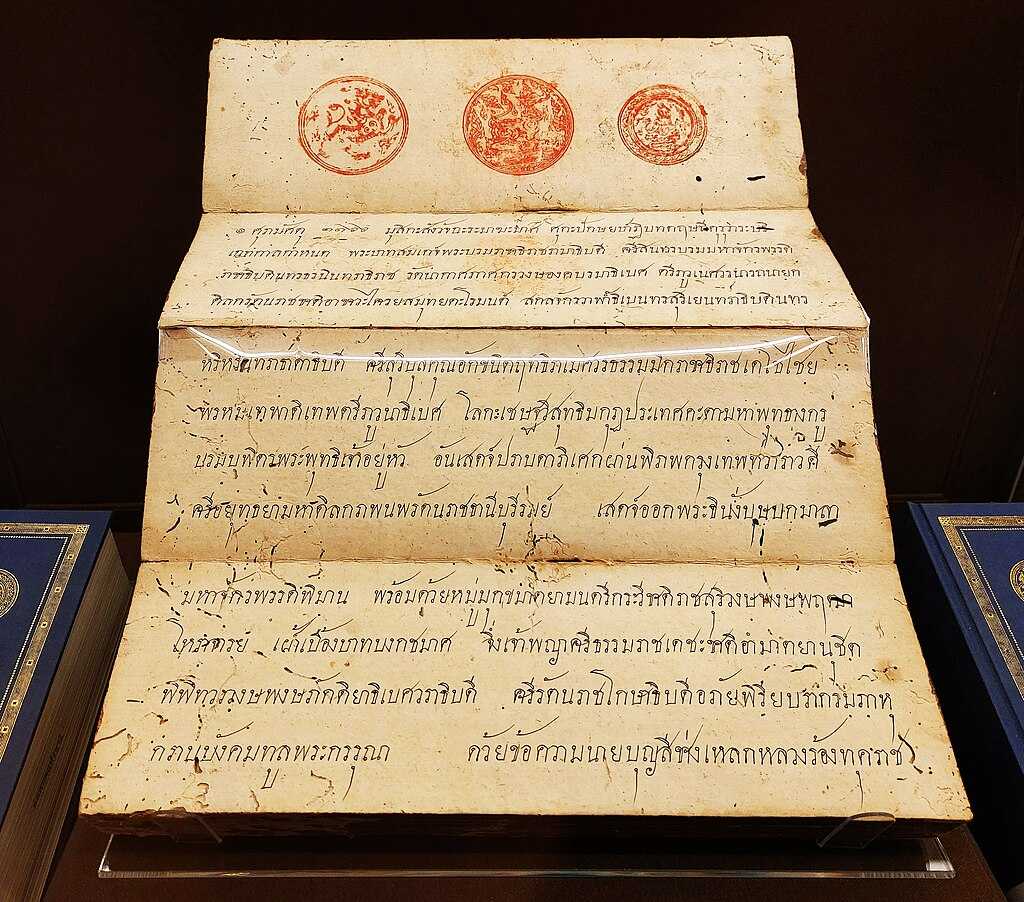

The progression from traditional law to modern law certainly hinges on the linear notion that the country moved from one broad type of “law” to another. This view was challenged when Baker and Phongpaichit recently argued that Siam’s traditional law, known as the Three Seals Code, should not be seen as legislation, but as an archive of socio-legal history. According to Baker and Phongpaichit, it would be illusory to impose our modern understanding of law and law-making on historical texts such as the Three Seals Code which, in their view, should be viewed as a historical archive reflecting the gradual accumulation of court rulings and decrees, as well as poetry, word play, and homily.5

This led to their thought-provoking suggestion that the Three Seals Code perhaps should not be treated as “law”, as far as law may be broadly understood as a system of rules, since it possesses different characteristics and may serve a wider social function – such as teaching the public about desirable behaviours – rather than a narrow statutory function.6 Instead, it may be considered as an archival compilation of written evidence of the evolution of legal conceptions.

Therefore, we should adopt a more flexible analytical framework when examining Siam’s reform process and recognise the true nature and characteristics of the subjects under study within their specific contexts. Certainly, it is more convenient to compare like with like – that is, one type of “law” with another type of “law”. However, such an approach may inadvertently obscure a richer, more nuanced understanding of legal history.

But if the law itself was elastic and layered, who or what were the “tectonic forces” – i.e. the agents shaping its form and direction?

Law-Shaping Lawyers

Another layer that adds to the tectonic landscape of Siam’s law reform comes from what Alan Watson called “Law-shaping Lawyers”, by which he referred to a group of the legal elite who shape the law either through their involvement in the legislative process or through the creation of precedents or authoritative legal interpretation.7 In a context of legal transplants, which Siam’s legal reform may be seen as, Watson argued that the law which emerged from the process tended to be strongly influenced by the knowledge of this group of lawyers, by their imagination, training, and worldviews.

The case of law-shaping lawyers in Siam is most fascinating. Tamara Loos acknowledged the transnational and transcultural nature of Siam’s legal reforms, as a number of foreign legal advisers from the East and the West worked alongside Siamese lawyers in shaping and implementing various changes.8 We have also taken an interest in the roles in which lawyers from the common law world helped shape the law reform process of Siam, a civil law country.

In our work on a comparative history of the courts of justice, we found that during the reform period, many British lawyers were appointed to the highest court of the land (and also to lower courts, but judgments of these were not recorded, rendering this a difficult topic for research), sitting alongside French, Japanese, and Siamese judges.9 We argued, among other things, that their legal backgrounds and professional experiences – such as their previous work as barristers in Britain or judges in British colonial territories – may have influenced Siam’s legal development, through their methods of legal analysis and application. However, their strong common law influence during the formative years of the country’s “modern” legal era was counterbalanced by the civil law influence from the French and Japanese judges. This is but one aspect of the hybridity of Siam’s reform process.

» In a context of legal transplants, Watson argued that the law which emerged from the process tended to be strongly influenced by the knowledge of a legal elite, by their imagination, training, and worldviews. «

In another article focusing on vicarious liability law, we argued that Thailand’s current main provision on vicarious liability (section 425 of the Civil and Commercial Code) may have been an incidental legal transplant from English law, influenced by the main Siamese drafters at the time, who were educated in England.10

Other “Law-shaping Lawyers” may be found in the Law Drafting Committee (currently known as the Office of the Council of State), the Ministry of Justice, and among personnel of other government departments such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of the Interior, as well as foreign advisors to the government. Together, they established the country’s legal structure and navigated the devious course of modernisation in the shadow of colonial threats.

All these facts point to the importance of understanding the key persons behind each legal phenomenon in order to truly unpack the layers and spheres of influences affecting the change.

How Should We Approach the Multi-Layered Reform Process?

This blog post marks an early step in what we hope will be a sustained exploration of the rich and layered field of legal history. From among many facets of this complex process, we explore two aspects which yield two key lessons. The first is to be open-minded to a challenge to an accepted norm – such as the question if traditional law was “law” at all. Another lesson is to understand a process not only from its impetus, but also from the people who turn its wheels. In the case of Siam, internal motivations and domestic spheres of influence help form a wider and more holistic view of the process. An emphasis on colonial threats is never the whole story – just one tectonic force.

- Andrew Harding, “Comparative Law and Legal Transplantation in South East Asia,” in Adapting Legal Cultures, ed. David Nelken and Johannes Feest (Hart Publishing, 2001), 205. ↩︎

- See Preedee Kasemsup, “Reception of Law in Thailand—a Buddhist Society,” in Asian Indigenous Law: In Interaction with Received Law, ed. Masaji Chiba (KIP Limited, 1986), 267–300. ↩︎

- Another eminent Thai scholar who shares a similar view is Professor Kittisak Prokkati (see Kittisak Prokkati, The Reform of Thai Law under European Influences (Winyuchon, 2013), 55 (Thai language)). ↩︎

- Note that other scholars may hold different views. For instance, R. Lingat divided Thailand’s legal development into four periods: the Ayutthaya period, the early Bangkok era (reign of King Rama I to early reign of King Rama IV), the Reform Period (reign of King Rama IV to reign of King Rama V), and the current period marked by the use of main codes of law (codification period). Robert Lingat, History of Thai Law (1935), 83-84 (Thai language). ↩︎

- Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit, “The Child is the Betel Tray: Making Law and Love in Ayutthaya Siam,” Thai Legal Studies 1 (2021): 1-21. ↩︎

- Ibid. 11-13. ↩︎

- Alan Watson, “Comparative Law and Legal Change,” CLJ 313, no. 37(2) (1978): 322-328. ↩︎

- See Tamara Loos, Subject Siam: Family, Law, and Colonial Modernity in Thailand (Silkworm Books, 2006), 29-71. ↩︎

- Surutchada Reekie and Adam Reekie, “British Judges in the Supreme Court of Siam,” in Thai Legal History, ed. Andrew Harding and Munin Pongsapan (CUP, 2021), 103-121. ↩︎

- Adam Reekie and Surutchada Reekie, “The Long Reach of English Law: a Case of Incidental Transplantation of the English Law Concept of Vicarious Liability into Thailand’s Civil and Commercial Code,” Comparative Legal History 6, no. 2 (2018): 207-232. ↩︎